A Memoir of Packets, Passion, and Packet Sniffers

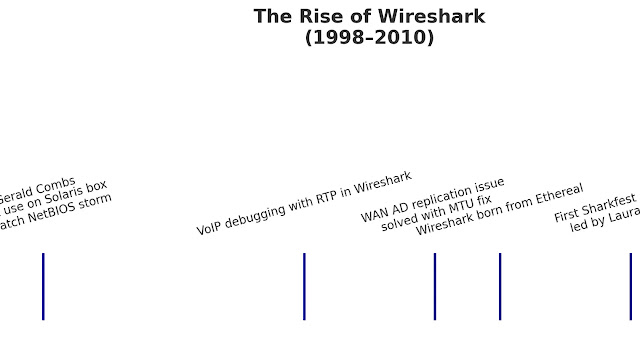

It was 1999. The air inside the data center smelled like ozone and burnt toast, a fragrance cocktail only sysadmins and network engineers can truly appreciate. I was hunched over a battered Sun Ultra 10 workstation running Solaris, its amber-colored terminal blinking like it knew something I didn’t. Ethernet cables snaked across the floor like digital vines. Somewhere in the network jungle, a rogue NetBIOS storm was wreaking havoc.

My tools? A cup of vending machine coffee, a pair of slightly rattled nerves, and a little open-source gem called Ethereal — the precursor to what the world would come to know and love as Wireshark.

I didn’t know it at the time, but that night on the data center floor with knees sore, face lit by the terminal glow, I was falling in love with the raw poetry of network packets.

The Rise of Ethereal and Open-Source Ether Magic

Before Wireshark became a household name among engineers, it was called Ethereal, and it was magic in the form of C code. Created in 1997/1998 by Gerald Combs, Ethereal filled a gaping void in the network troubleshooting world. Commercial sniffers were expensive, clunky, or locked behind proprietary paywalls. Ethereal, on the other hand, was free, friendly, and freakishly powerful.

Running it on a Solaris box in 1999, I remember being mesmerized. Packets weren’t abstract blobs anymore. They were ordered, chatty little diplomats traversing subnet borders, stumbling, retrying, succeeding. Ethereal gave them voice, structure, and context.

That NetBIOS storm? A misconfigured Windows 95 box chat-blasting the LAN with name registration packets every millisecond. I wouldn’t have caught it without Ethereal’s detail pane showing the beautiful chaos frame by frame. That night, I captured the moment not just in logs but in memory.

2003: A VoIP Ghost in the Machine

Flash forward to 2003. I was now a battle-tested network consultant, carrying a ThinkPad loaded with Red Hat, tcpdump, and of course, Ethereal. One client — a fast-growing B2B company — was experiencing ghostly VoIP dropouts. Calls would start fine and then, halfway through, voices would vanish like they’d walked into a black hole. Cisco TAC had no answers. The vendor blamed the firewall. The firewall blamed the switches. The switches sulked silently. I ran a packet capture directly on a span port. SIP, RTP, jitter, DSCP markings — they all lined up like the suspects in an episode of CSI: Network Edition. It turned out a misconfigured QoS policy was silently demoting real-time packets, causing jitter so severe it clipped audio beyond recognition. Ethereal, with its RTP stream analysis and jitter graphs, laid it bare like a confession under interrogation.

Once again, it wasn’t the most expensive tool, but the most insightful one that cracked the case.

Enter Laura Chappell: The Packet Whisperer

If Ethereal was the brush, then Laura Chappell was the artist who taught me how to see the canvas.

Laura didn’t just explain protocols — she made them breathe. Her early tutorials, distributed via CD-ROMs and online packets of wisdom, were like treasure maps. Each lesson turned an opaque IETF spec into a palatable and often humorous detective story. She made TCP flow analysis feel like watching traffic choreography. SYN, SYN-ACK, ACK — the holy trinity of connection initiation — became almost liturgical in her voice.

When Wireshark was born in 2006 (renamed from Ethereal due to trademark issues), Laura doubled down. She founded Wireshark University, and later, Sharkfest — a kind of summer camp for packet nerds held in Northern California. I attended my first Sharkfest in 2008, held on the campus of Stanford University. It was unlike any tech conference I’d ever been to. People weren’t just there to flex certifications. They were there to share war stories, decode packet captures like forensic sleuths, and swap jokes only Layer 2 aficionados would laugh at. Laura was at the center of it all — part teacher, part rockstar.

Of Bits, Bytes, and Floors

One of the more brutal nights of my career came when troubleshooting a stubborn Active Directory replication issue over a WAN in 2008. Domain controllers in two different geographies refused to talk. Logs pointed fingers in all directions. Tensions were high.

I ended up sleeping — well, half-sleeping — on the datacenter floor, Ethernet in one hand, bag of chips in the other, running packet captures until my eyes blurred. And then, at 3:47 AM, the pattern emerged. Fragmented packets. MTU mismatches. AD traffic was being chopped into pieces too big for the router to handle. The culprit? A misconfigured router interface that ignored the proper 1500-byte Ethernet standard. No ICMP “fragmentation needed” messages because someone had blocked them. No retransmits. Just quiet, silent drop-offs.

Wireshark didn’t just help me find the problem. It helped me understand it. It whispered the truth of what the machines were trying — and failing — to say.

The Culture of Packets and Hackers

The late 90s and early 2000s in Northern California were a magical time. The internet was still young enough to be idealistic, but mature enough to get interesting. Hacker culture wasn’t about ransomware or crypto exploits — it was about understanding. About sharing tools and building together. Open-source projects like Ethereal/Wireshark were extensions of that ethos. They weren’t built for profit. They were built because someone said, “There’s got to be a better way.” Gerald Combs started something. Laura Chappell gave it voice. And the rest of us? We found community.

In dusty server rooms and sunlit conference halls, we shared packet captures like mixtapes. We debugged slow applications by reading TCP window sizes. We learned to love latency, retransmissions, duplicate ACKs — not as problems, but as stories. Every packet a message. Every stream a dialogue.

Ode to my friend

Of all the bytes and bits I’ve decoded over the years, some of the clearest memories are not packets, but people. And one in particular: my Canadian friend and colleague from those Perot Systems and Dell Services years, roughly 2004 to 2011. We worked side by side in the Plano campus, a fortress of air-conditioned hum and fluorescent glow, but it was our camaraderie that truly made that place warm. He and I spent countless hours shoulder to shoulder, peering into Wireshark traces with the intensity of two detectives trying to decode the nervous system of a living network. DNS timeouts, misbehaving IKE handshakes, inexplicable MPLS encapsulations — we dissected them like surgeons. Often, we’d run a capture, sip vending machine coffee, and look at each other with a raised eyebrow that said, “Well, that shouldn’t be there.”

But it wasn’t just the packets. We talked about everything. Physics. Quantum entanglement. The elegance of tunneling protocols. How Einstein would have probably hated NAT. And in the quieter moments, we’d speak of our immigration journeys — his Canadian roots, my own H1B visa adventures, the labyrinthine path to a Green Card in a land where we were building digital highways but still unsure if we belonged.

Our walks around the Plano campus were a ritual. Laptop bags slung over our shoulders, we’d step out into the Texan sun, escape the server fans and firewall configs, and just walk. Talk. Think aloud. Some days we solved network problems. Other days, we solved nothing, just shared the weight of life’s packet loss.

He passed away far too soon. A beautiful mind — warm, sharp, unpretentious. There are moments when I open Wireshark, see a malformed packet, and half-expect to hear his voice over my shoulder: “Well, there’s your problem.” And then I remember, quietly, that he’s now beyond all handshakes, acknowledgments, and retransmissions. But the echo of those conversations, that shared curiosity, that sense of being seen and understood amid a sea of protocols — those things never timeout. They persist, flowing silently through the fabric of memory, like a perfect trace that never drops a frame.

Mid 90s to mid 2000s — A few books that propelled me to be a Network Engineer

While others in the late 90s were quoting lines from The Matrix, I was quoting hex dumps. While Silicon Valley chased IPO dreams and the world discovered the web through clunky dial-up tones, I was knee-deep in the blood and bones of the Internet — packets, headers, and protocols that spoke a language I was learning to read fluently. I wasn’t just a network engineer — I was an archaeologist of Ethernet, peeling back layers of encapsulation to uncover buried truths.

In that era of my life, I had two sets of holy scriptures. Not metaphorically — literally. Two copies of TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1: The Protocols by W. Richard Stevens. One lived permanently at my office desk, pages worn and coffee-stained from long troubleshooting sessions. The other traveled with me — at my apartment, in corporate housing, sometimes propped open on a hotel nightstand when I was on an extended assignment. Stevens’s words weren’t just technical; they were elegant, precise, and alive. He made packets poetic. Each diagram, each TCP state transition, was a revelation. He showed that networking wasn’t merely a utility — it was a living, breathing system of cooperation, timing, and trust.

But Stevens wasn’t my only sage. As I ventured beyond protocol behaviors and into the beating heart of Internet routing, I found myself enraptured by the works of John Moy. His books on OSPF — the Open Shortest Path First protocol — were masterpieces of clarity and intent. OSPF could have been a mess. Instead, thanks to Moy’s vision and articulation, it became a standard I respected deeply. Reading his work felt like sitting beside the protocol’s creator as he explained why it behaved the way it did, why it preferred certain neighbors, how it chose its paths. It wasn’t just theory — it was design, distilled. Then came Sam Halabi’s Internet Routing Architectures — my initiation into the mystique of BGP. That book taught me that routing on the Internet was not just about algorithms. It was about politics, policy, hierarchy, and architecture. BGP wasn’t a protocol — it was diplomacy. Autonomous systems exchanging reachability information with a suspicious squint and a reluctant handshake. Halabi gave me the lens to see the Internet not just as wires and packets, but as a global organism, stitched together by contracts, competition, and cooperation. Between Stevens, Moy, and Halabi, I had not just technical manuals — I had philosophy, strategy, and a deep appreciation of the invisible scaffolding that held the digital world upright. Their books were my companions during late nights and long weekends, my reference points during outages and deployments, my mentors in a field that often felt like decoding a secret language. The books propelled me towards my certification quests, starting with TCP/IP in the Novell Netware, through numerous Cisco certifications to Juniper and Arista Certs. Those tomes weren’t just about networking. They were how I became a network engineer.

Final Capture

Looking back now, with networks abstracted by SDN and traffic tunneling through VPNs and mesh overlays, it’s easy to forget that once upon a time, we saw the wires. We heard the noise. We knew our networks the way a mechanic knows an engine — by sound, by smell, by feel.

Wireshark was our stethoscope. Laura Chappell/Gerlad Combs were our teacher, our Sherpa into the OSI model’s icy crevasses. And for me, a nerd with a Solaris box and a packet storm in 1999, it was the beginning of a lifelong fascination.

I still fire up Wireshark occasionally — not because I need to, but because I want to. Like revisiting a childhood street or re-reading a favorite book. Each packet, a memory. Each capture, a story.

In a world that increasingly chases the next abstraction, there’s something grounding about watching packets dance across the wire. Raw. Honest. Human.

Like Laura always said: “Packets don’t lie.”

Amen to that.

Comments

Post a Comment